[Members’ News] – Renewables are booming in Vietnam. Will the upswing last?

Vietnam’s upcoming power development plan is set to scale up its trajectory towards clean energy. Experts say the plan’s success will depend on energy planners’ ability to integrate renewables into the power system.

Will renewables keep thriving in Vietnam when grid challenges and looming policy uncertainties have left industry players on tenterhooks? Image: Pixabay

For market watchers observing Vietnam’s energy landscape, the nation’s upcoming electricity development blueprint is set to be the strongest sign yet of how fast the country strives to move towards renewables in the decades ahead.

The highly anticipated Power Development Plan VIII (PDP8), expected after the general elections next month, will reshape Vietnam’s energy market in a bid to reduce its reliance on fossil fuels, ensure energy security, and cut carbon emissions.

But even as Vietnam leads the charge in Southeast Asia’s energy transition, long-standing barriers including policy uncertainties, weaknesses in the country’s market design and transmission capacity risk hurting clean energy growth in the coming years, undermining its development targets.

Grid woes

Arguably the biggest problem looming over the market is the country’s underdeveloped power grid, said Vaibhav Saxena, foreign counsel at Vietnam International Law Firm (VILAF).

The explosive growth in solar power in recent years has put stress on transmission infrastructure, with overloads often forcing, Vietnam Electricity—EVN—to restrict how much power operators can feed into the grid.

Cuts in power delivery result in immediate financial losses for project firms as the state utility only pays for the electricity that its grid can accommodate.

Vietnam’s electricity grid is the elephant in the room.

Giles Cooper, partner, Allens

Saxena said while the PDP8 lists ambitious clean energy targets, the plan’s success hinges on Vietnam’s ability to integrate renewables into its electricity system. “You can install as much generation capacity as you like, but what’s the point if the electricity produced cannot be off-taken?”

“Vietnam’s electricity grid is the elephant in the room,” said Giles Cooper, a lawyer at Allens, a law firm in Vietnam. He added that despite progress made, it remained unclear how upgrades would be financed at the scale needed in the years ahead.

Daniel Haberfield, an Australian lawyer based in Vietnam with law firm Duane Morris LLP, said Vietnam had acknowledged the need for private sector capital to further develop its grid infrastructure. But under the country’s current electricity legislation, EVN has a monopoly over power transmission and distribution, making private sector financing of grid infrastructure a complex legal undertaking.

But, he said, things may soon change. In January, the country introduced its first uniform Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Law, potentially paving the way for private sector participation in the nation’s grid expansion. In February, Vietnam’s Politburo issued Resolution 55, recommending amendments to the Electricity Law to allow for private sector investment in power infrastructure.

Some experts have proposed potentially easier ways around such legal obstacles. Saxena said establishing a renewable energy fund through mandatory fees paid on top of each energy investment could provide the funding needed for grid development while mitigating risks for developers.

In its latest draft version of PDP8, Vietnam’s Ministry of Industry and Trade (MOIT) estimates that US$52 billion of investment will be required for grid infrastructure upgrades over the next 15 years. Vietnam’s first privately sponsored transmission line, funded by Vietnamese renewable energy firm Trung Nam Group, came online last year.

Legal headaches

Grid congestion is not the industry’s only concern. Developers have long lamented about Vietnam’s power purchase agreement (PPA), a contract that developers must enter into with the buyer of the power they generate. In Vietnam, that’s either EVN or one of its subsidiaries.

As in other markets, Vietnam’s PPA is a standard-form document; while clean energy companies can negotiate with EVN to include additional terms, it is difficult to amend the agreement’s core terms.

Saxena said Vietnam’s PPA was not consistent with international best practice in several key areas. Risks enshrined in the document create unfavourable conditions for renewable energy projects, hurting their ability to draw investment.

“The PPA is one of the most important documents that lenders look to when determining whether or not a project is bankable, or within their risk appetite,” said Haberfield.

Among key issues is that lenders are not granted step-in rights, he explained. In more mature markets, financiers that provide project funding usually seek an express right to step in where the project company is unable to adhere to its obligations.

Where the project company faces bankruptcy, complex litigation, or is otherwise unable to complete a project, the right to take control of the project vehicle and remedy a breach of contract on behalf of the company can potentially salvage a project.

“This is a very important mechanism if you want to attract tier-one international lenders, but it is not expressly provided in Vietnam’s current PPA,” said Haberfield.

Developers have also grappled with the PPA’s narrow view on projects’ commercial operation date, he continued. Under Vietnam’s green energy pricing schemes, project firms have been entitled to a fixed feed-in tariff paid for the electricity they generate before a specified deadline.

But Vietnam’s definition of commercial operation date does not take into account situations where a project is ready to pass on power but cannot yet connect to the grid. This means that construction delays caused by EVN, even if out of the developer’s control, can cost investors dearly.

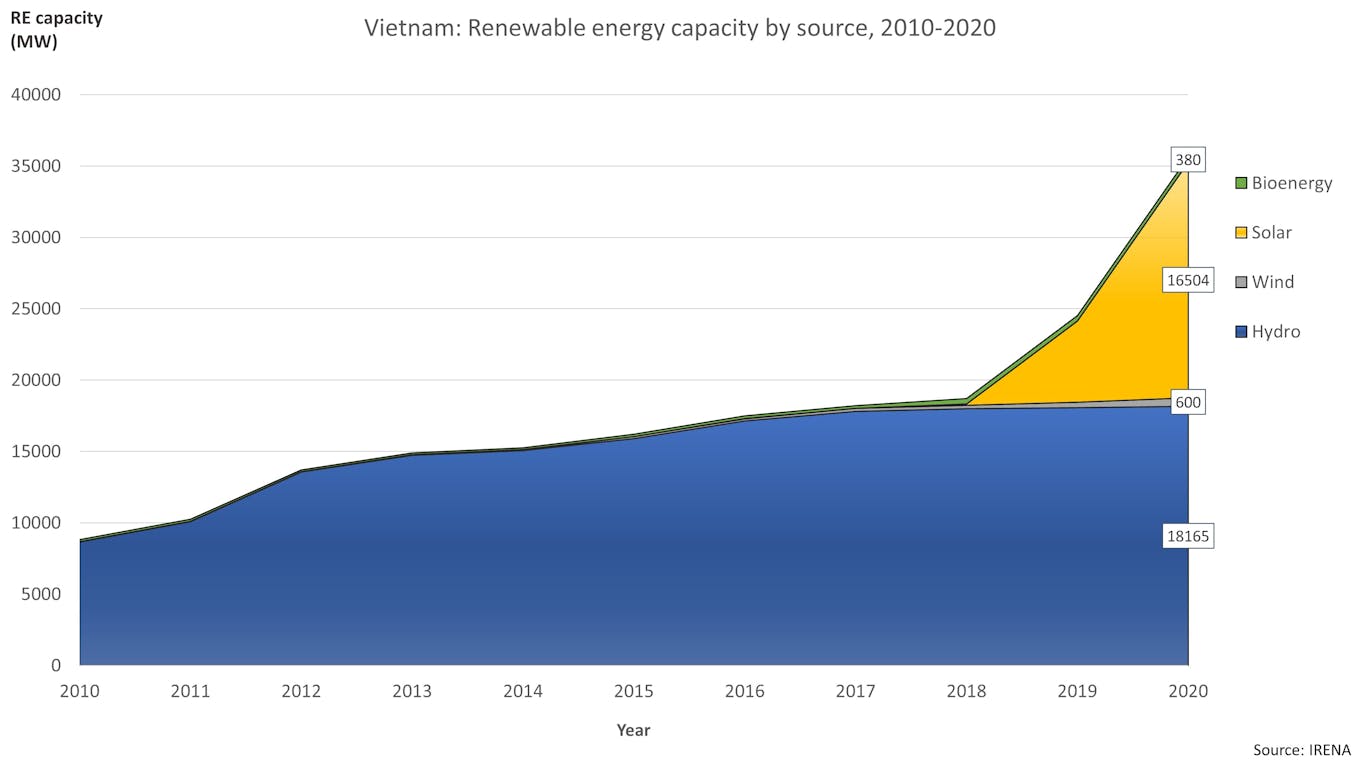

Eco-Business graphic: Renewable energy deployment in Vietnam by source, 2010-2020. Source: International Renewable Energy Agency

Risks don’t end when projects are up and running. Developers aren’t given any government guarantees for EVN’s payment for the electricity they deliver or on foreign exchange rates. Since feed-in tariffs are denominated in local currency, investors risk incurring losses due to currency fluctuations, said Haberfield.

Finally, the contract prevents independent power producers from seeking legal recourse at an impartial arbitration institution outside Vietnam in the event of tarrif disputes or payment delays, he said.

Cooper said Vietnam could greatly benefit from improvements to its PPA, particularly if the country’s energy planners can replace feed-in tariffs with an auction regime.

Auctions would enable Hanoi to select the most price-competitive developers for specific projects. Such schemes have led to record-low electricity prices around the world, including in Southeast Asia.

Cooper said that more conducive market conditions would attract big international banks and more seasoned utility companies that have previously shied away from doing business in the country.

As a result, green energy prices would likely plummet, especially when investors have to factor in fewer financial risks, he explained.

Murky market

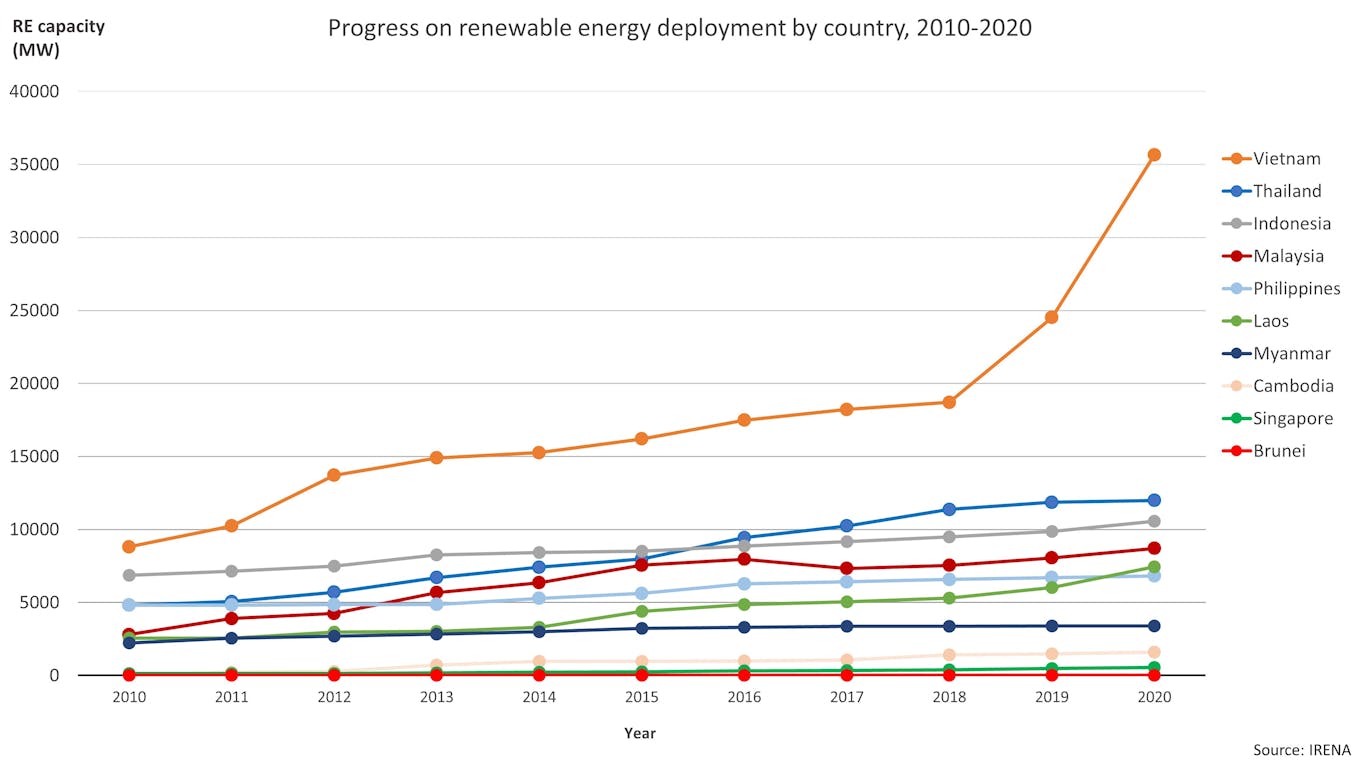

Despite persistent challenges, Vietnam has managed to catapult itself into a leadership position for renewables in Southeast Asia. Offered favourable tariffs and tax incentives, developers and lenders have rushed into the country, resulting in market growth previously unthinkable in the region.

Eco-Business graphic: Vietnam installed more renewables than all its Southeast Asian neighbours combined last year. Source: International Renewable Energy Agency

In 2019, Vietnam installed a record capacity of renewable energy, with solar power jumping from 105 megawatts (MW) to 4,898 MW. Last year, total renewable capacity increased to nearly 36 gigawatts (GW). Solar capacity grew by 11.5 GW, with rooftop solar accounting for about 9 GW of the increase—the third-biggest growth in rooftop solar installations globally in 2020.

Vietnam’s PDP8 outlines major energy policies through to 2045. The current draft wind target stands at 18-19 GW for 2030, with a solar target of 19-20 GW. Together, solar, wind and biomass are projected to make up more than 32 per cent of the nation’s total power generation mix by 2030, up from about 10 per cent in 2019. Coal is expected to account for 27 per cent.

By 2045, the plan envisions a total power generation capacity of 277 gigawatts, of which renewables are forecast to provide nearly half. By then, renewables are expected to supply most of Vietnam’s electricity (32 per cent), with coal accounting for 31 per cent, and gas for 26 per cent.

Investors can wait for a few years, but they will eventually lose patience.

Vaibhav Saxena, foreign counsel, VILAF

But persistent grid challenges and policy uncertainties may choke investment and risk undermining the country’s racing progress in renewable energy.

Cooper said Vietnam has been silent on the details of the policies required to reach its ambitious clean energy goals.

In 2017, the country’s trade ministry introduced a feed-in-tariff for solar that generated significant interest among investors, especially in the country’s sunnier southern regions.

However, the second round of the immensely successful programme ended last year. While it appears certain that Vietnam will switch to an auction scheme, the industry has yet to see a final draft of the policy. The MOIT recently submitted an updated draft decision on rooftop solar regulations, but it is unclear when Hanoi will greenlight the proposal.

A similar plight is facing the wind industry. Last year, the MOIT proposed to extend the feed-in tariff scheme from November 2021 until the end of 2023 to alleviate concerns that developers might miss this year’s deadline due to regulatory challenges and pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions. However, the policy is still under consideration.

Saxena told Eco-Business if grid upgrades continued failing to keep pace with renewable energy development, the country risked falling out of favour with industry players.

“Investors can wait for a few years, but they will eventually lose patience. Once they start leaving the country, foreign investment could fall. This would not be good for Vietnam’s economy,” he said.

Retrieved from here.